Many companies are still experiencing acute talent shortages that are seriously impacting business results. While the immediate focus for most leaders is aptly on filling the sometimes staggering number of open positions as quickly as possible, we should also ask ourselves why we have openings in the first place, and what can we do about it. You can keep pouring new employees into the top of your talent bucket, but it does no good if there’s a hole in the bottom through which people are leaking out.

The “Great Resignation” (the term first coined by Anthony Klotz of Texas A&M for this phenomenon) is interesting, but I’m not convinced that employees still don’t leave companies, they leave managers. In any event, multiple recent studies by Microsoft, Gallup, and Persio suggest that it’s not over. Losing key talent can be devastating for any organization; for small and mid-sized businesses, where “departments of one” are common, it’s especially severe.

We’re talking of course about retention. There are five serious mistakes that I see organizations and leaders make when it comes to keeping people. Let’s address these deep-rooted and misguided beliefs we have about employee retention and discuss strategies for keeping your best people.

Friendly warning: Most of what follows goes against both the conventional wisdom and common HR practices. So buckle up.

Mistake #1: Treating people the same.

Let’s say there are 100 employees at a company, all at various levels in the organization. In the last six months, 14 of them have resigned for jobs elsewhere and there are rumors that others might also be looking around.

The company’s HR person loves KPIs and is sounding alarms. “If this trend continues, our annualized turnover rate will be over 25%!! We’re already struggling to find people in this market, not to mention the institutional knowledge we’re losing and the direct and indirect costs of getting new people trained up. Danger, Will Robinson! Danger!”

I’m just gonna say it. In every organization, some individuals and jobs are more important than others. High performers matter more than low performers, and there are hard-to-replace jobs and easy-to-replace jobs. Does that turnover KPI tell us how many of the leavers were high performers in critical jobs? It does not.

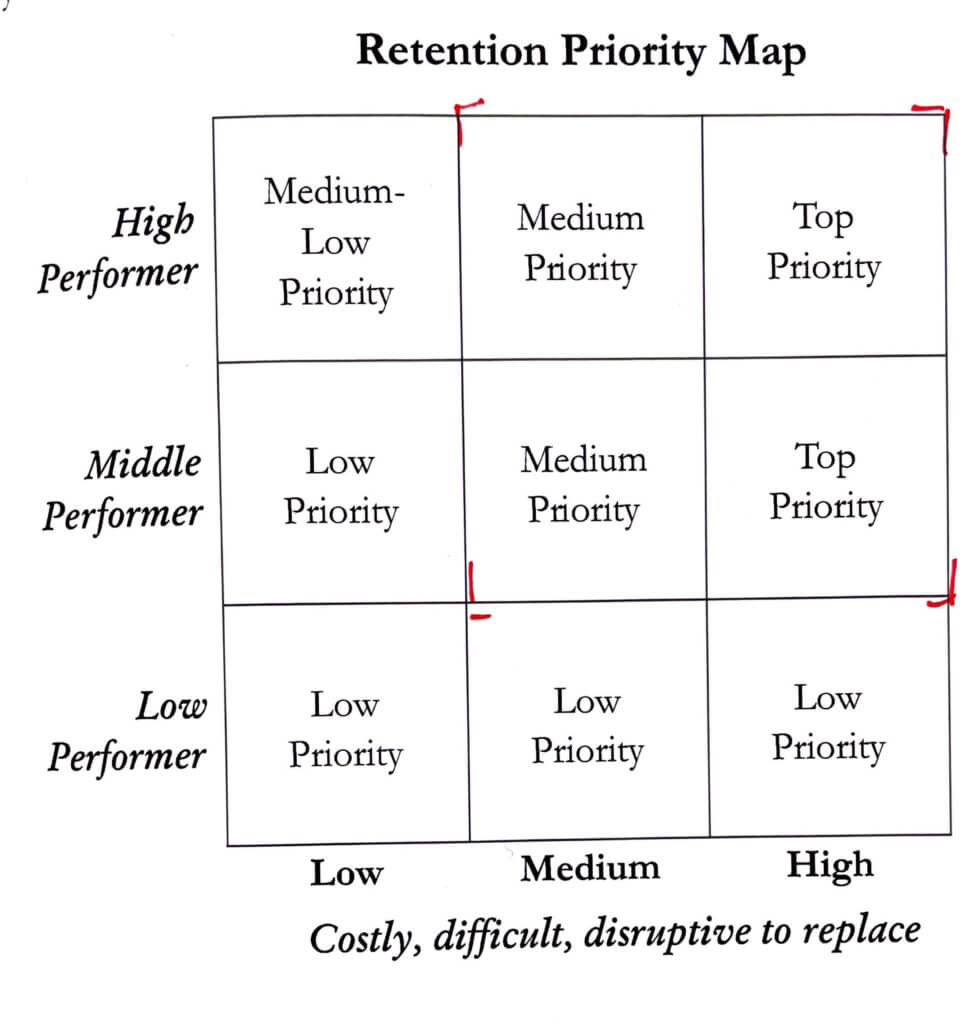

Say hello to the Retention Priority Map.

This nine-box table is a tool that tells you where to put your retention attention. And here’s an interesting twist: A rock star in an easy-to-replace role is actually a lower retention priority than a middle performer in a hard-to-replace role.

So stop calculating overall turnover, because it doesn’t tell you where to focus your retention efforts. Clarity on who your key people and critical positions are does.

Mistake #2: Believing that your company-wide initiatives actually retain employees.

At your company let’s say you know each employee’s height, weight, and age, and you find that the average employee is 5’6½” tall, weighs 157.7 lbs, and is 41.3 years old. News flash: There’s a pretty good chance that employee, with those exact numbers, doesn’t actually exist.

This is the “average person” fallacy and it’s screwing up your retention efforts. You’ve increased pay, updated benefits, renovated that nasty-ass break room, and sent your supervisors to anger management training (damn it). So why are people still leaving? It’s because the reasons people quit are unique to each individual. There’s no “primary reason” for why people are quit a job, so it follows that there’s no one-size-fits-all solution to fix that leaky talent bucket.

Truth bomb: It ain’t about the money. Multiple studies have shown that while managers overwhelmingly believe that employees quit for higher pay, more than 90% employees, regardless of level and pay, tell third-party researchers that money had little or nothing to do with their decision to leave. Quitting a job is uncomfortable, so this is the easiest, least confrontational reason for employees to give their bosses when quitting. And we fall for it, every time.

(Sidebar: It’s fascinating to me when leaders also cite money as the singular reason for their people voluntarily quitting, despite the readily available data to the contrary. I suspect they lean on this reason for the same reasons employees do: Not only is it terribly uncomfortable when employees grade on one’s management skills with their feet, but it’s also terribly visible, which can be a serious blow to one’s self-confidence, and if one’s boss is paying attention, maybe even cause anxiety about job security. Convincing oneself that “they left for more money” perhaps deflects and externalizes the apparent cause of the employee’s departure away from the leader, obscures the potential leadership development areas that need shoring up, and absolves the leader from taking any personal responsibility for addressing the real concerns that led the employee to resign. In short, we lean on the pay crutch to protect ourselves, and others, from seeing how much we suck. Now there’s a PhD dissertation topic for someone.)

There’s only one retention technique that works universally. Want to know why people stay or leave? Ask them! It costs nothing, and the companies where this is a way of life (I worked at one for six and a half years) don’t have turnover problems. Their secret weapon: managers engaging regularly with each employee one-to-one.

The good news is it’s not rocket surgery, but it is but it’s a radical concept that makes some leaders uncomfortable. So what questions do you actually ask? Author and speaker Mark Murphy suggests the following questions to use for discovering why people leave:

- Do you know any employees who have left?

- Do you know why they left?

- What are the 2-3 things you think other people like least about working here?

- What’s your take on the reasons people are leaving?

When the meetings get a little more comfortable, the manager should then ask these:

- In the last 90 days, can you tell me about a time you felt really unmotivated or demotivated?

- If somebody asked you about the single worst part of working here, what would you tell them?

- Has there been a point in the past 90 days when you felt like leaving? What caused it?

- Have you thought about quitting?

- Are you thinking about quitting?

- If you felt demotivated again, would you feel comfortable sharing that with me?

You can also ask similarly worded questions about why people stay:

- What are the 2-3 things you think other employees like about this organization?

- In the last 90 days, can you tell me about a time you felt really motivated or excited?

- When was the last time you felt motivated?

- What got you excited?

- What are the 2-3 things you like best about this organization?

- Why do you think employees stay at this company?

- Can you tell me about why you join the organization?

- If you had to tell somebody about the single best part of working here, what would it be?

- Is there anything that would improve your working experience?

- How do you feel about your opportunities for success here?

- Is there anything that would improve your working experience that you think is out of my control?

These are scheduled conversations, for 20 minutes minimum, held at least quarterly (although monthly is way better). Do this regularly with those employees who are top and medium priorities on your matrix from above. Take notes. Compare notes with other managers. Fix what needs fixin’.

And if you have people you’d love to see pursue excellence elsewhere, well, those are different kinds of conversations. Or maybe none at all.

Every leader must commit to this approach, from the CEO on down. Some leaders are afraid that asking these kinds of questions puts ideas in people’s heads about quitting. That’s like not going to the doctor because you might get bad news. The doctor’s visit doesn’t cause the illness. We can bury our heads in the sand and hope our employees don’t quit, or we can take their temperature and start working on ways to retain them.

Mistake #3: Neglecting the first three months.

Turnover rates in the first 90 days of employment are higher than for any other period. The impressions that employees form even in their first 30 days have been shown to be accurate predictors of their eventual tenure with the company.

Over my career, when joining a new organization, I’ve seen some truly powerful approaches to on-boarding techniques, and some downright appalling ones. The experiences that will always stay with me are the ones when (1) I felt wanted, welcomed, and prepared to join the new company, and (2) I felt like I was part of the new family.

Making new hires feel wanted

Before they even start, there’re things you can be doing. Here’s a checklist of actions that will enhance your retention of new employees.

- Get or make a “Welcome” card. Then have all employees in the department sign it, and send it to the employee’s home.

- Send some key reading material. Not too much, just the employee handbook and maybe some key marketing materials. Once they start the job they’ll be busy, so this is the time when they’re much more likely to be excited about learning the necessary background info about the company.

- Send a roster of their team or department. Just a basic “who’s who,” nothing too overwhelming. Names, titles, years of service, one bullet about their job function for each team member, and then something off the wall like their favorite vacation or concert or pets. The key here is to give the new employee something both memorable and humorous.

- Better yet: Zoom. You could also do a “meet-n-greet” virtually via video. In 2011 (long before COVID!) my family and I moved to Switzerland for my work and my older daughter’s class at the new school did a meet-n-greet via Zoom. It was marvelous and incredibly helpful for my daughter’s transition, and she’s still besties with several of those kids to this day. So fun.

Welcome new hires to the fold

Nothing says “Sorry, we forgot about you” like starting at a new company without a computer, ID badge, and place to sit ready for you. Yikes!

In addition to getting those painfully basic items right and ready, here are some things to do on your new employee’s first day that will set you apart from most other employers:

- Make the morning about the new employee, not about orientation paperwork. Make sure a member of his team meets him when he arrives, preferably his manager.

- Make the first few hours matter. We’ve all seen nature documentaries where a hatchling or newborn animal bonds with the first creature it sees, even if it’s not its own species. Make every effort to ensure the bulk of the new employee’s morning is spent with his manager.

- Introduce him to his on-boarding buddy. The inherent power dynamic prevents a new hire’s manager from being his buddy, so pair him up with a peer. This person’s role as an on-boarding buddy is to help guide the new person and ensure he gets oriented to basic procedures, like paychecks, phone system, good lunch places, etc. (and to make sure that the new person has a constant social connection for his first six months).

- Make his arrival a big deal. People usually leave their previous employers with a certain amount of celebration, so it’s important to welcome them with the same amount of fanfare. At one new job I had, the tradition was for the manager to arrange for a hospitality cart with a huge vat of coffee along with donuts to be delivered to the employee’s office at a set time, to which all team members and other relevant internal people were invited/required to stop by for a “welcome open house.” Talk about making quick connections! It was simply perfect.

- Make Week 1 memorable. Continuing the theme of equal fanfare, organize a lunch out or a pizza party during the new person’s first week. It’s also a great idea to have the owner or CEO (or someone very close to the top) swing by and say hello during his first week (make sure the senior leader knows his name). Nothing conveys caring and excitement about having the new hire in your organization more than when a busy executive stops by to welcome them to the family.

As a new employee settles in to his first three months, it’s still a fragile period. This is the best time for managers to forge a relationship that will really last. At the end of the first month, I suggest you do an informal review of how things are going. Waiting 90 days is too long to wait for this conversation. Into months two and three, continue to help your new employee build relationships with colleagues and peers, and connect regularly to check learnings and progress.

Mistake #4: Allowing people to leave without a fight.

If you lost a valued client, you’d be calling them, visiting them personally, sending gifts, basically doing everything it’d take to woo them back. Yet many leaders are surprisingly passive or even downright avoidant when an employee say that she wants to leave the organization.

When an employee tells you she’s resigning, don’t subscribe to the adage, “If you love somebody, set them free.” Turning again to Mark Murphy, he suggests a three-step process that will help you to lure your valued employees back. The main purpose here is to slow them down during the resignation process.

As mentioned in Mistake #2, resigning is uncomfortable. Your employee wants the conversation to be quick and painless, she wants to feel relief from this anxious and nerve-wracking situation. Thus it’s the manager’s job to keep her from feeling relief, to keep her in an emotionally-conflicted state, where she might change her mind. So when she first drops the bomb, don’t let her leave your office or get off the phone; the manager’s goal is to keep her in the “discomfort zone” as long as possible.

Step 1: Withhold relief

First, as soon as you get the news, stop what you’re doing and hold a “listening session” immediately. This is when you’re going to visibly stop, look, listen, and question. Find a quiet space to have a private conversation right away. Get the whole story. Gather as much information as possible, but stay neutral and open-minded.

Ask the employee not to tell anyone about her decision, until you’ve worked out the details together. This comes with a 24-hour waiting period, which means asking the employee to hold off on her decision and meet again in 24 hours, when you can present her with all her options.

Finally, end the listening session with kudos. Affirm to the employee her value and contributions to the team and that’s why you want some time to present the best options to her. Then pronto, get in touch with your boss and brainstorm about what you can do or offer to keep the employee from leaving.

The degree of sense of urgency you demonstrate during this first step will be viewed by the employee as a sign of her value, to the extent that, if you’re quick about it, she may even start thinking twice about her decision to leave.

Step 2: Make your offer

The next-day meeting will be you, the employee, and someone higher up (i.e., a senior executive whose presence will help convey that this is a very serious matter). Prepare for this meeting by building valid arguments that demonstrate how staying with you is the employee’s best option. (Of course, if there’s absolutely no compelling argument for her to stay, then you’ll have to accept defeat.)

Present your offer and make it enticing to the employee. Be sure to address the specific reason you heard the day before about why the employee wants to leave — you have to solve this problem or else she’s gone.

Once you’ve presented your offer, ask the employee for a final decision. But sometimes there are tricky roadblocks to a “yes, I’ll stay.”

Step 3: Confront roadblocks

Often there are other factors affecting the employee’s decision, such as the spouse’s concerns or agenda, or the kids’ school situation, or the new company putting on the hard sell.

Talk to the spouse directly and seek to answer their questions and concerns. Selling the significant other on the value of staying is sometimes just as important as selling it to the employee.

Dealing with the other company who’s poaching your employees is another matter. The best approach I’ve seen is to give the employee a rather formal script to use for declining the offer from the other company. You should try to be in the room for that call, to the extent the employee is comfortable with that. The benefits are (1) this competitor will think twice next time about stealing your employees, and (2) the employee’s decision to stay is locked in, both verbally and psychologically.

You gotta fight to keep your great employees. Companies that drop everything to listen to employees who want to leave and sincerely try to fix things to keep them end up retaining about 50% more people than other companies who do nothing. Just sayin’.

Mistake #5: Writing off leavers.

When a valued employee leaves, sometimes we feel betrayed or even angry. After all, it took a lot to hire her, her contributions were awesome, and we were grooming her to take over some day. But now that she’s given notice, we’re pissed. So we cut all ties. Finito. Done with you. Forever.

This might feel good emotionally in the moment, but I’ve seen firsthand, recently, how this cripples leaders long term. The reality is that high-performing ex-employees make great re-hires. They also can become great referral sources for both business and talent, or can even go on to become great future clients. It’s all about helping them to leave on good terms and to remember how much they liked working for and with you. There are three simple ways to keep things positive and end the working relationship while maintaining a connection: Throw a party, touch base, and share updates.

First, throwing a farewell party leaves your departing employee feeling emotionally connected to his co-workers and cements the bond to your company. Second, touching base with an ex-employee by phone or email 30 to 60 days after leaving to see how things are going keeps that emotional connection going. Finally, periodic updates about new products, openings, and the like keeps channels open. Ex-employees are perfect for talent and business referrals because they already know your business and what it takes to be successful there.

Employee retention happens in the trenches of your workplace, not in management team meetings. If you truly commit to correcting the mistakes you’re making with these simple strategies, I predict you’ll see a difference in 30 days, maybe even less. You don’t need to pay your people more money to keep them – try paying them more attention.